Guest post by Simon Sedorenko of the New York Film Academy

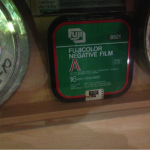

It often comes as a surprise to modern audiences that there are still a great many movies being shot in celluloid and stored in quaint little cans; these days, everyone assumes everything is digital. But to an increasing number of filmmakers with a mind for practicality, those cans are anything but quaint – they’re murderously heavy, technically limiting and, above all, expensive.

Naturally (and perhaps unfortunately), for most projects it all boils down to the crisp green notes. It doesn’t matter whether the resulting film looks and sounds terrific if the cost of production makes it unviable, and lack of funding remains the primary reason why many great projects never even make it past the business planning stage. Thankfully, digital HD is a medium that neither sacrifices quality nor pushes expenditure through the roof; with digital filming costs rapidly dropping and post-production dramatically more efficient, it’s almost becoming a no-brainer.

Naturally (and perhaps unfortunately), for most projects it all boils down to the crisp green notes. It doesn’t matter whether the resulting film looks and sounds terrific if the cost of production makes it unviable, and lack of funding remains the primary reason why many great projects never even make it past the business planning stage. Thankfully, digital HD is a medium that neither sacrifices quality nor pushes expenditure through the roof; with digital filming costs rapidly dropping and post-production dramatically more efficient, it’s almost becoming a no-brainer.

While a good filmmaker with a passion for creating quality work will generally prosper regardless of what camera you put him or her behind, the decision to go digital often comes with an array of benefits that not many feel able to return from. It also hasn’t taken long for the upper echelons of the industry to realize this, either – excluding the early tentative forays into digital, it only took ten years from the first hugely mainstream feature length movie to employ HD digital (1999’s The Phantom Menace) to it becoming commonplace, with 2009’s Slumdog Millionaire and Avatar breaking records, winning awards and making a heck of a lot of cash in the process.

And again, back to the production cost element; one of the Phantom Menace’s producers asserted that they would have spent around $1.8m on film alone if they’d gone down the analogue route, whereas in reality they only spent $16,000 on its digital counterpart.

Similarly, it costs a mere $150 to press and ship a digital copy of a movie to a theater compared to the $1,500 it takes to do the same for a single film copy.

Revolution Up, Down, and Back Up the Entire Chain

It’s not that celluloid has come into derision. We’d hazard a guess that most filmmakers would love carry on shooting everything analogue, and nearly all old-schoolers regard film with a certain level or respect and nostalgia. But nostalgia may well be the realm it is resigned to; If the whole weight of Hollywood is shifting towards HD digital and smaller-budget filmmakers are now finding it way more affordable than film, it’s really only going to go in one direction.

With the majority of large studios moving towards digital for cost reasons, all that’s left is for theaters to catch on. Indeed, the pressure is already on – many theaters scrabbled to update their equipment for the aforementioned Avatar which demanded a digital projection room for screening. The latest figures suggest that as of last year 64.5% of domestic theaters as of 2012 are equipped with digital projectors, which mirror global trends (at 63%) according to the IHS Screen Digest Cinema Intelligence Service. They go on to predict that 35mm projection rooms will decline to just 17% of all theaters around the world by as soon as 2015.

With the majority of large studios moving towards digital for cost reasons, all that’s left is for theaters to catch on. Indeed, the pressure is already on – many theaters scrabbled to update their equipment for the aforementioned Avatar which demanded a digital projection room for screening. The latest figures suggest that as of last year 64.5% of domestic theaters as of 2012 are equipped with digital projectors, which mirror global trends (at 63%) according to the IHS Screen Digest Cinema Intelligence Service. They go on to predict that 35mm projection rooms will decline to just 17% of all theaters around the world by as soon as 2015.

This as corporate heavies are turning to the more practical (and affordable) medium of digital and putting pressure on theaters to follow suit, this will feed back up the chain to indie filmmakers and students in cinematography school – the content creators of tomorrow who will propagate the medium and end up making great digital filmmaking the industry standard.

Sadly, there will be a few inevitable casualties, namely the smaller theaters who can’t afford to keep up with technological changes. But the net benefit to the industry will be a far reaching one, affecting both lovers of movies and those who create them alike. Theaters themselves will do well out of the shift too after getting over the initial overheads, gaining from cheaper equipment maintenance (compared to often decades-old analogue projectors) and easier film storage and.

Another possible ancillary benefit is that if the profit margins for theater admissions is improved by reducing expenses, audiences may see theaters rely less heavily on other ways to recoup costs – ergo, less on-screen ads and cheaper popcorn. This is probably a bit of a stretch, though.

Any Chance of a Film Revival?

Retro is chic right now. Case in point: we’re already seeing sales for vinyl music booming as people yearn for a more ‘authentic’ experience.

But this is a false equivocation when it comes to film. Vinyl does offer a more tactile experience for the user and is arguably a superior from an audible standpoint; if a user can foot the added expense, choosing vinyl is a savvy choice for the serious audiophile.

Unless the moviegoer has a projection room in their home, however, the same cannot be said of film. The end result of digital film is indistinguishable from (if not better than) analogue, especially given that most people still working in film are trying to replicate the flawless look of HD digital in post-production anyway.

In short, perceived differences are becoming increasingly blurry and there is no added value offered to the end user as long as the film is shot well.

There will always be film ‘purists’ (such as Christopher Nolan who shot The Dark Knight Rises in 35mm or Paul Thomas Anderson, who shot The Master mainly in 65mm). And long may they continue espousing the craft – After all, variety is the spice of life and we’re certainly not fans of elitism or telling anyone how they must enjoy or carry out filmmaking.

There will always be film ‘purists’ (such as Christopher Nolan who shot The Dark Knight Rises in 35mm or Paul Thomas Anderson, who shot The Master mainly in 65mm). And long may they continue espousing the craft – After all, variety is the spice of life and we’re certainly not fans of elitism or telling anyone how they must enjoy or carry out filmmaking.

But whichever way you look at it, digital filmmaking is long past the misconceptions of it being a ‘watered-down’ version of traditional cinematography and has rightfully earned a place within the industry.

And, ultimately, it’s not likely to decline in popularity going forward.